Awareness, innovation shape future for those living with rare disease, ASMD

PAID FOR BY SANOFI GENZYME

Awareness, innovation shape future for those living with rare disease, ASMD

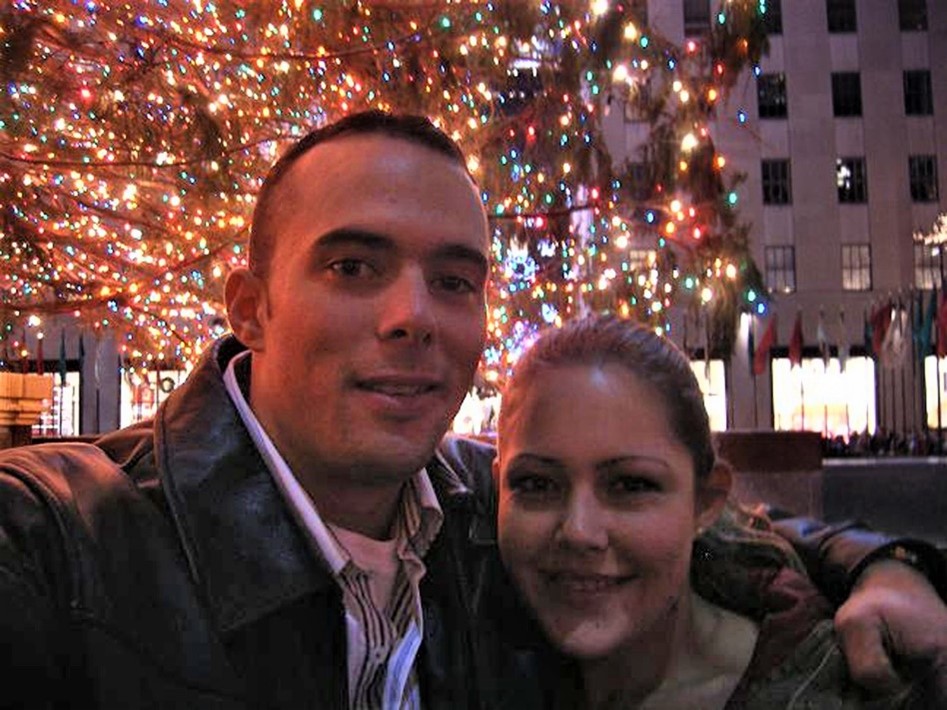

When April talks about going on dates with her husband, Chris, or watching fireflies with their 6-year-old son, Nicholas, she radiates in such a way that all but betrays the battle happening inside her body.

But as the Texas mom balances family life, she also manages a rare, progressive, and potentially life-threatening genetic disease known to cause health consequences — including an enlarged spleen or liver, difficulty breathing, lung infections and unusual bruising or bleeding, among a multitude of other disease manifestations.

Historically known as Niemann-Pick disease A and B, acid sphingomyelinase deficiency (ASMD for short) affects only 1 in 250,000 individuals. And because it is so rare, ASMD can be difficult to diagnose and has no available treatments. Though with scientific innovation and greater awareness, a path to a quicker diagnosis may be possible.

Invisible illness

Diagnosed with ASMD at age 2, April remembers how going back and forth to see doctors as a child was something her brothers and sister didn’t have to do.

“I remember asking my dad about it,” she said. “And my dad said, ‘You’re our special kiddo and we have to take special care of you. ”The disease didn’t prevent her from having a happy childhood, she said, even as it did begin to affect her body, internally. April remembers swimming and playing tennis as a child, but not being allowed to play contact sports or roughhouse with her siblings. Then, at 11, she stopped growing and her abdomen became severely enlarged, altering her body shape – a common occurrence among those living with the disease.

“So, the kids in elementary school weren’t too nice,” she said. Still, she persevered. She knew some dreams – like growing up to fly an Army attack helicopter – might have to be readjusted. But others might still be within reach.

When April was 14, she saw her first specialist who was an expert in ASMD, and remembers having two burning questions:

“My first question was, ‘How long can I live?’ Then, before the doctor could even finish her answer, I asked, ‘Can I have children?’ Growing up I had always wanted to be a mom someday.”

Many years, procedures and doctor visits later, and after marrying Chris, an active-duty member of the U.S. Army, April would get her wish.

“Nicholas was our miracle baby,” April said. “And Chris is my biggest supporter. He’s always there. He is my rock.”

Diagnostic odyssey

For many people, having a rare disease like ASMD often means a painstaking journey before eventually finding the correct diagnosis. Meanwhile, patients with ASMD feel the effects of the disease progression, which can range from cirrhosis of the liver to crippling fatigue.

Dr. Melissa Wasserstein, a board-certified biochemical geneticist and pediatrician, has been working with ASMD patients for decades. Now chief of the division of Pediatric Genetic Medicine at the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore and professor of Pediatrics and Genetics at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, she has come to know many patients and their families over the years – each a reminder of the toll this “diagnostic odyssey” can take.

“There often are months if not years that go on where somebody’s in limbo-land trying to figure out what’s happening. It’s often a very anxiety provoking and expensive time,” she said.

“I’ve certainly had patients over the years who have come to me diagnosed with something else, only to discover that they actually had ASMD. For example, (telling a patient) ‘You actually don’t have Disease X that you thought you had your whole life; we now know it’s ASMD.’ … It’s challenging to make that diagnosis unless you are familiar with ASMD – and many people aren’t familiar with it, even in the health care community.”

That’s something that Wasserstein and organizations such as the International Niemann-Pick Disease Alliance are trying to change.

Sandy Cowie, an occupational therapist who serves as INPDA president, was also diagnosed with ASMD when she was 2 years old. In her role, she helps the INPDA in achieving its mission to facilitate progress and increase awareness in Niemann Pick Disease by amplifying the voice of the ASMD community in areas that have cross-border impact.

Working to raise awareness of ASMD (especially with clinicians who may be the first point of contact on the diagnostic journey) to help facilitate earlier diagnosis is one way the organization serves patients.

“Because symptoms of ASMD can be very variable and can present at varying times … it can make it very challenging to get an accurate diagnosis,” she said. “They may have been bounced from a family physician to a hematologist, to a liver specialist, to an oncologist, depending on what their symptoms were when they first presented. And sometimes, especially for kids, they’re just told, ‘Well, they’ll grow out of it.’ … Being able to reduce the timeline for diagnosis would be a huge benefit for people.

“We definitely know that early diagnosis leads to earlier intervention and better outcomes,” she said.

Wasserstein agrees.

“We don’t want people suffering and we don’t want the disease to progress,” she said. “The goal long-term is to have a safe and effective treatment so the disease progression does not become irreversible.”

A future of hope

With recent advances in medical science, change may be on the horizon.

A broad network of people – scientists, researchers, clinicians, advocates and those living with ASMD – have helped to reach this point and Wasserstein applauds them.

“It has been a lot of work,” she said, “but it has also been a major commitment by the ASMD community. They have been so incredibly brave and incredibly generous with their time.”

One area that is helping shape the future of the disease are advancements in newborn screening. Wasserstein and Cowie agree that this could drastically shorten the diagnostic time for people impacted by ASMD.

Currently, every baby born in the U.S. has blood samples sent to their state’s newborn screening laboratory, usually the day after they’re born. Wasserstein and others are piloting the ability for newborns to be screened for additional disorders, including ASMD.

“If we can pick up babies before they have symptoms, they can avoid that diagnostic odyssey,” she said.

Similarly, she is also working on expanded carrier screening that would let would-be parents know whether they might carry the ASMD gene, which could be passed along to their children.

“(Parents) can be really helpful at minimizing that diagnostic odyssey in the future,” she said.

As innovations in science and technology advance, so do ways for the ASMD community to connect and support each other.

In 2013, an EU grant helped to initiate a project establishing the International Niemann-Pick Disease Registry. This patient-owned disease-specific clinical registry is useful in building a robust understanding of ASMD by facilitating ongoing progress in research, diagnosis, clinical management and potential avenues for future development, Cowie said.

“We’re very much trying to make it so that people aren’t feeling like they’re the only person battling on their own,” she said.

April said organizations such as the INPDA and the national and local groups it supports have made a massive impact in her life.

“Just having them there to bring you up and support you is a huge thing,” she said. “There’s a group of us out there who help each other with everything.”

Her advice to others living with ASMD or another rare disease?

“Stay positive; keep your chin up,” she said. “You are not alone.”

Cowie shares her sentiment.

“Persevere and keep hope,” she said. “I know that it is a rough road. The road is changing. It has changed a ton in the last 20 years. … We still have a long way to go, but we’re making huge progress.”

MAT-GLB-2103764-v1.0-10/2021